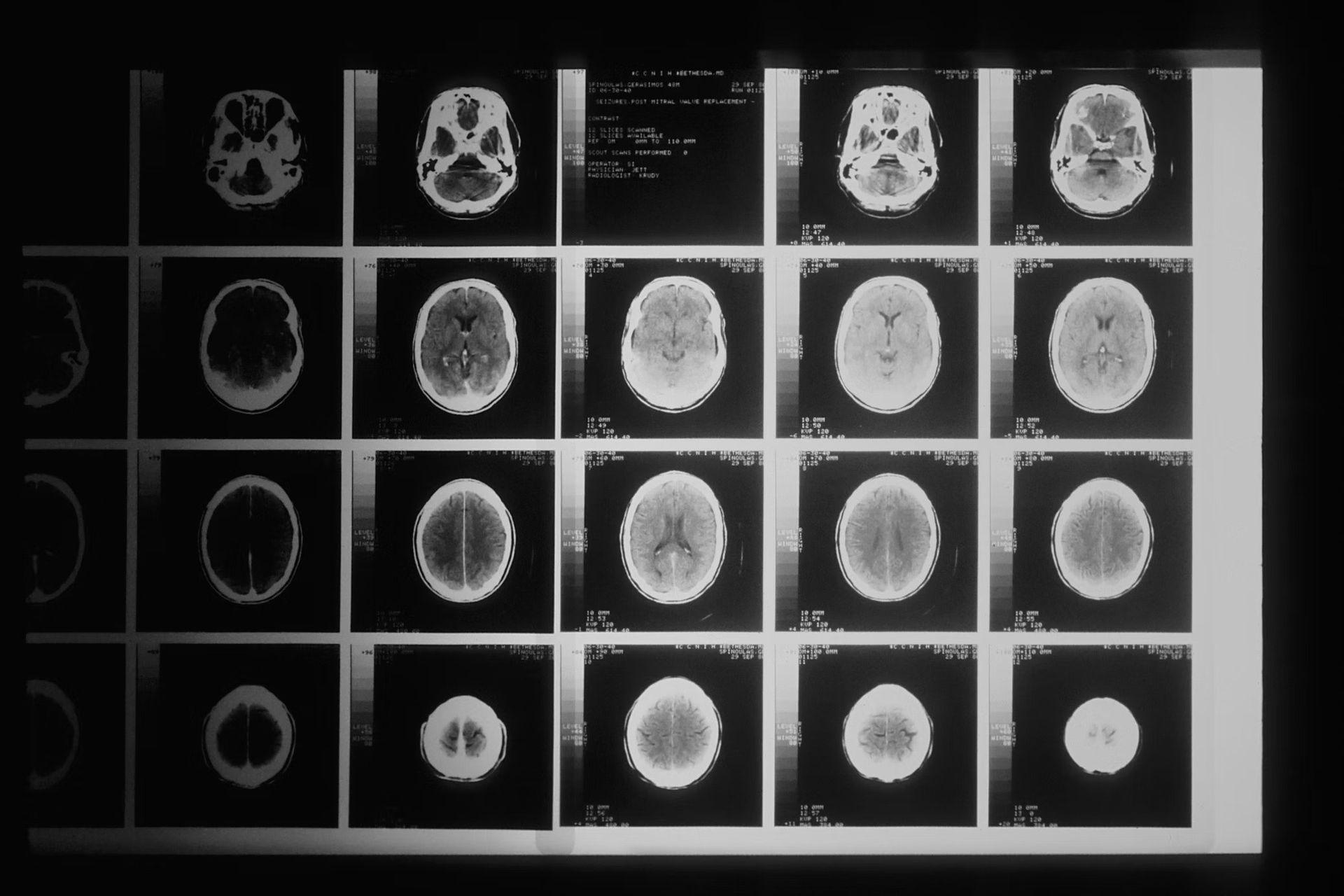

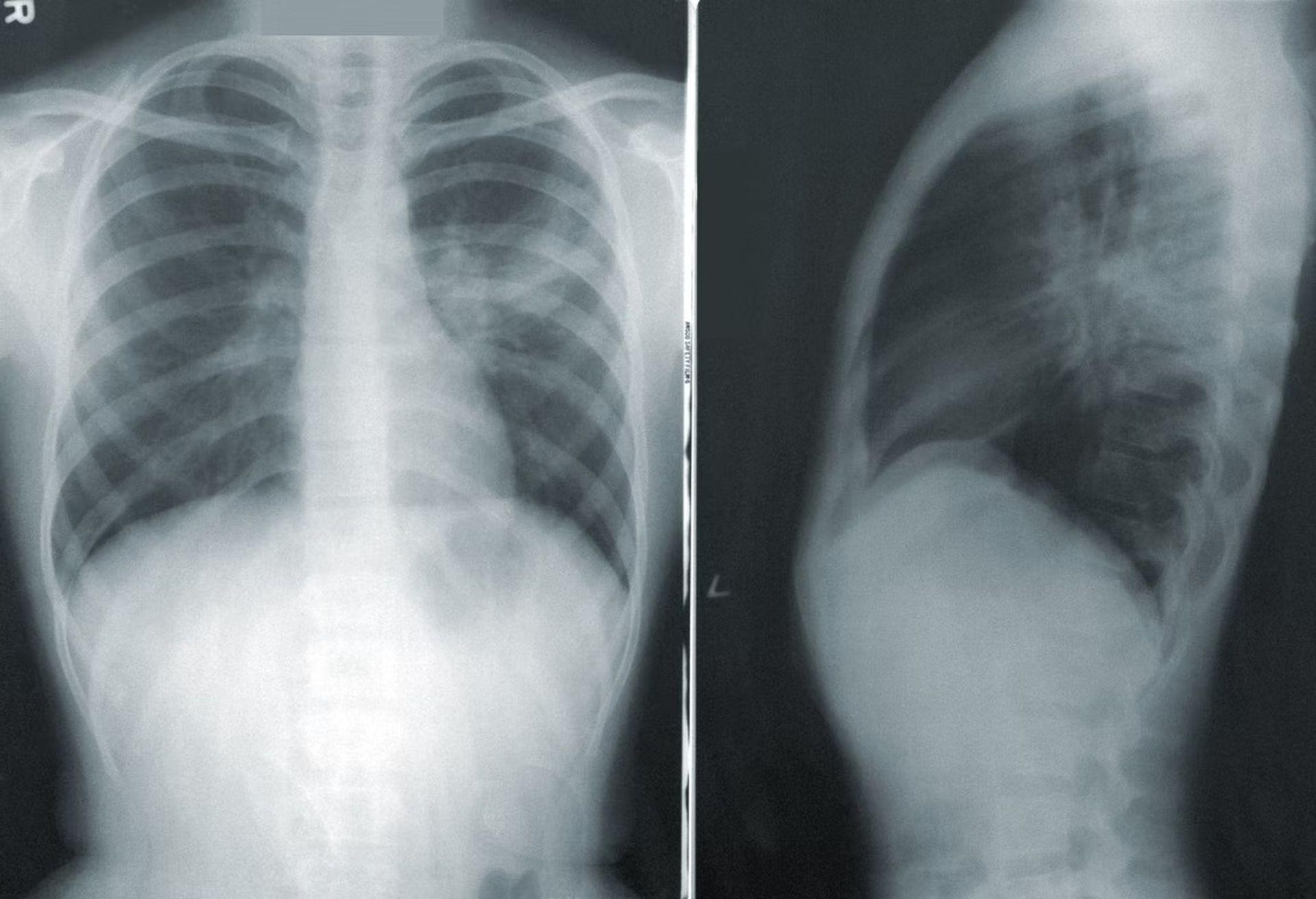

An international team of researchers from Canada, the United States, Australia, and Taiwan published a new study in which it is shown that an AI can tell people’s race from X-rays and CT scans with 90% accuracy. This is an enormous success because even professionals cannot tell a person’s race by looking at X-rays and CT scans. The scientists don’t know how the program can provide such accurate results.

Researchers are shocked with the results

“When my graduate students showed me some of the results that were in this paper, I actually thought it must be a mistake. I honestly thought my students were crazy,” said the co-author of the study, Marzyeh Ghassemi, an MIT assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science, Boston Globe reports.

After noticing that an AI software for scanning chest X-rays was more inclined to miss abnormalities in Black people, researchers began investigating. Artificial intelligence technologies have also started to be used in medicine. For instance, dentists are also utilizing such systems in the diagnosis process. Check out our article, “Filling or root canal treatment: Ask Overjet AI,” to discover more.

“We asked ourselves, how can that be if computers cannot tell the race of a person?” said the co-author of the study and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School, Leo Anthony Celi.

How an AI can tell people’s race from X-rays?

Researchers trained the AI system with many race-labeled pictures of various parts of the body, including the chest, hand, and spine — with no apparent racial identifiers such as skin color or hair type — before providing it with sets of unclassified photographs. With more than 90% accuracy, the AI can tell people’s race from X-rays using unidentified photos.

The breakthrough may assist medical personnel in certain ways. Still, it also raises the risk that AI-based diagnostic systems might inadvertently produce racially biased findings, such as automatically suggesting a specific therapy to Black patients, regardless of whether it is appropriate for them. Furthermore, the individual’s doctor would be unaware that the AI based its diagnosis on racial data.

The answer to the riddle, according to Ghassemi, lies in melanin, where X-rays and CT scanners identify higher amounts of melanin in darker skin and store this information in the digital image in some way that has gone unnoticed. More studies will be done on this; the hypothesis convinces not everyone. Perhaps X-rays and CT scans detect higher amounts of melanin in darker skin and save this data in some form that human users have never seen before. Ultimately, they think melanin is key to discovering how AI can tell people’s race from X-rays. It’ll take a lot more study to figure it out for sure.

Instead of demonstrating natural distinctions between ethnicities, Alan Goodman, a professor of biological anthropology at Hampshire College and coauthor of the book Racism Not Race, suggests AI detects differences caused by geography.

“Instead of using race, if they looked at somebody’s geographic coordinates, would the machine do just as well? My sense is the machine would do just as well,” Goodman explains.

No substantial racial distinctions in the human genome have been discovered, but there are significant variations between people based on where their ancestors originated.

In any case, Celi advised against using AI diagnostic technologies that might automatically produce prejudiced outcomes.

“We need to take a pause. We cannot rush bringing the algorithms to hospitals and clinics until we’re sure they’re not making racist decisions or sexist decisions,” Celi added. Researchers began focusing on artificial intelligence more and more, for example HyperTaste, an AI-based e-tongue analyzes the chemical composition of liquids.