Is it feasible to build a computer with a sense of taste? In response to this question, IBM Research scientists developed HyperTaste, a chemical taste sensing tool. It performs analyses and detects the chemical composition of liquids using its “electronic tongue” status.

Can computers have a sense of taste?

“HyperTaste was inspired by advances in AI and machine learning to mimic human senses like sight and hearing for recognizing images and interpreting speech. We wanted to present a new lens for chemical sensing,” explained Patrick Ruch from IBM Research, the coauthor of the study.

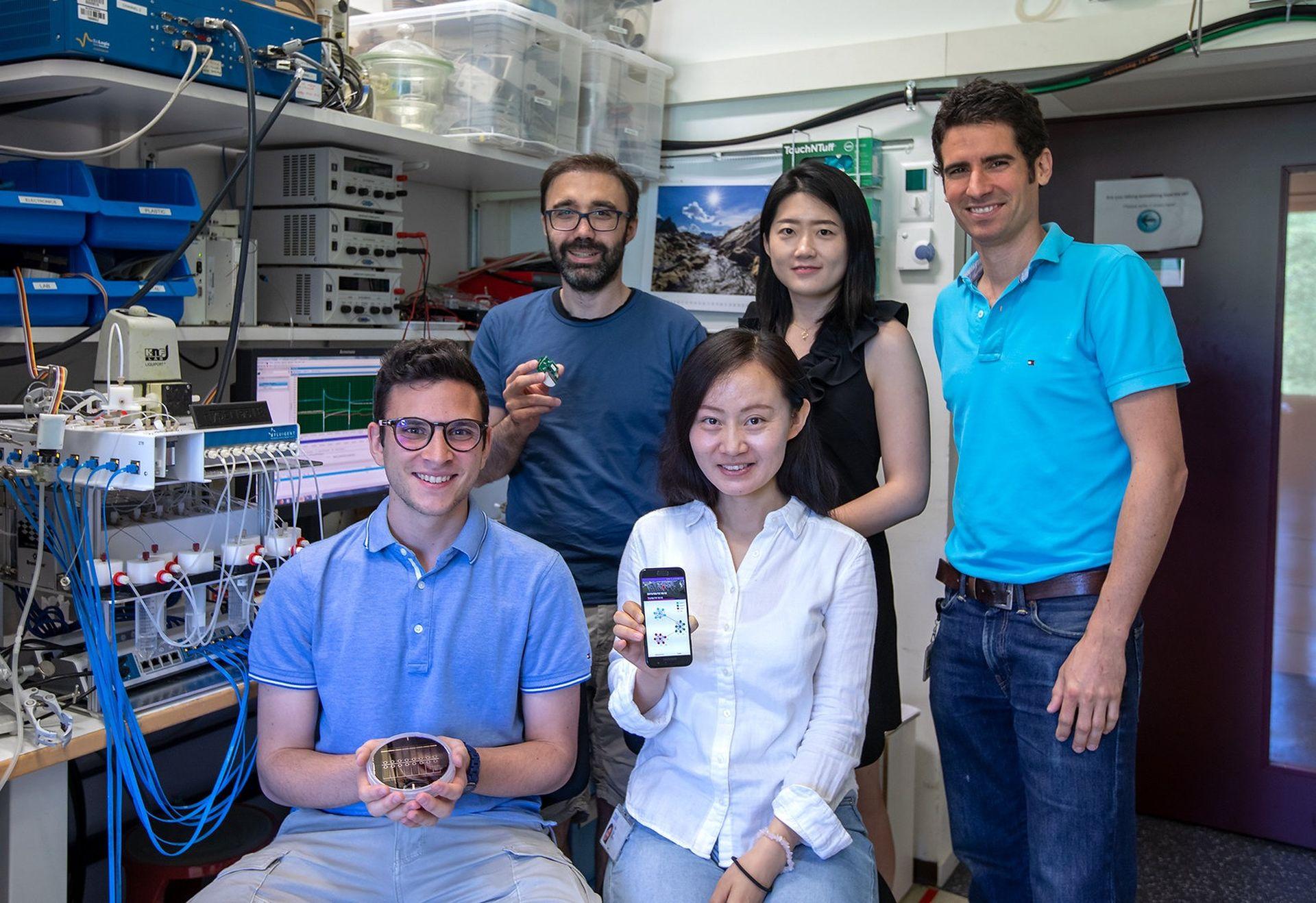

The goal was to apply a combinatorial approach, similar to that of our tongues’ many taste buds, and then use machine-learning algorithms to interpret the output of those sensors. The team used a printed circuit board with microcontroller-based hardware and a set of 16 conductive polymeric sensors that changed voltage when immersed in a solution. Researchers are continuously working on creating human-like computers; who will win the battle between artificial intelligence vs. human intelligence, can a game-changing technology play the game?

“It’s a bit similar to how a battery works, and it’s almost as if we’re using the liquid we want to test as an electrolyte,” said Ruch.

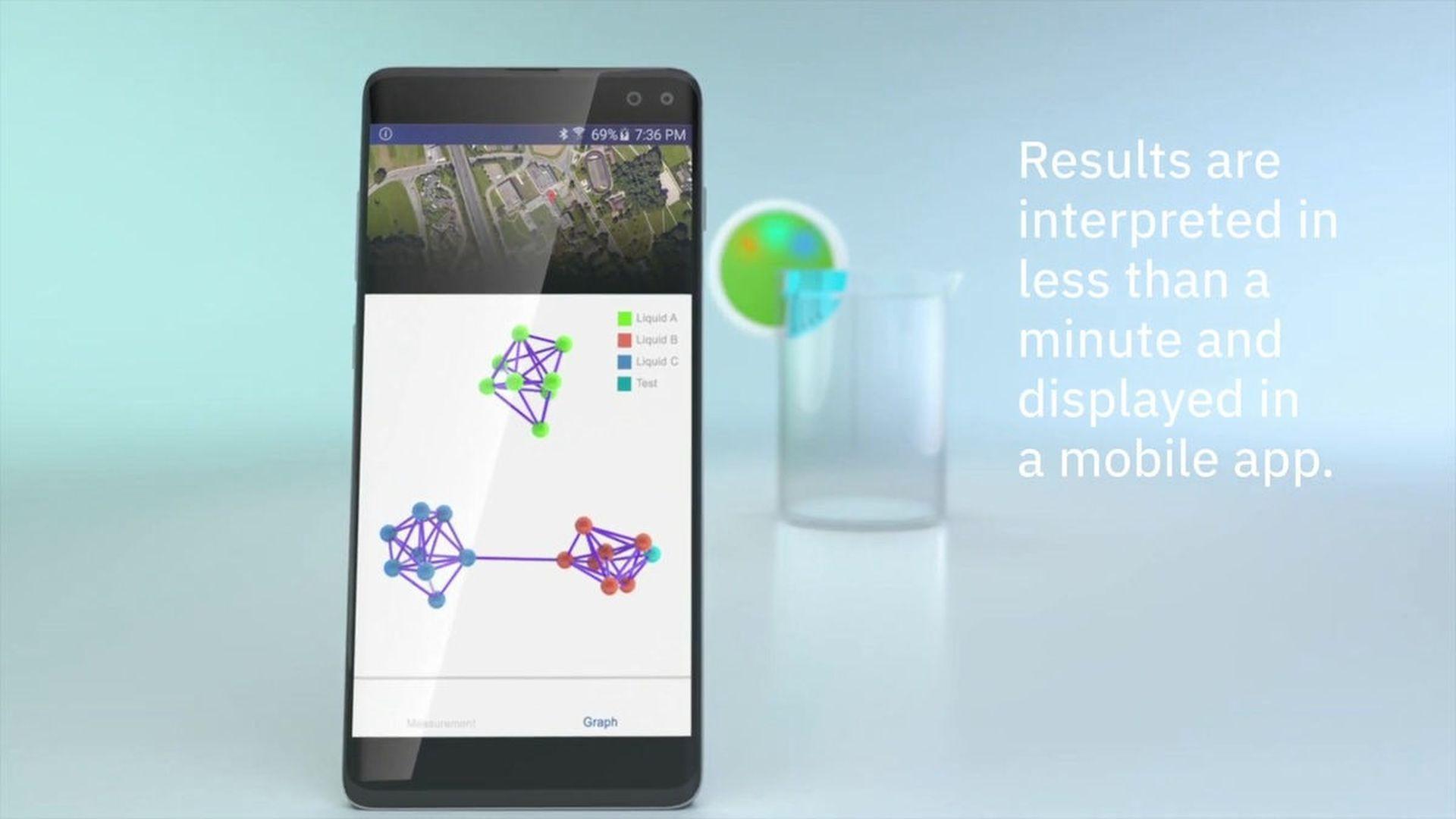

Each sensor in the array generates a stream of voltage signals unique to the liquid it is immersed in—its chemical fingerprint. These voltage signals are transmitted via a mobile app to a cloud server, where a machine-learning model trains and compares the signal with a database of known liquids. The algorithm then transmits predictions back to the application within minutes.

“You don’t necessarily require a lab to do this, saving on both time and cost and accelerating the testing process. We wanted to use minimalistic, portable hardware and demonstrate that the intelligence of such a chemical sensing system could be pushed to the software side,” explained Ruch.

Despite its simplicity, HyperTaste was a difficult project to accomplish. It’s challenging to combine the system’s many components as well as bring together an interdisciplinary team that includes electrochemists and material scientists to assess HyperTaste’s sensing mechanism, electrical engineers to design and build the hardware, and software engineers for data science and deployment.

“We had to integrate all these capabilities in the team and also find a common language to be able to understand the interfaces between these different components and the handoff points,” said Ruch.

HyperTaste isn’t meant to detect a particular kind of chemical; compared to other traditional chemical sensors such as pH and oxygen sensors, it isn’t intended to recognize a specific compound.

“If you want a precise quantification of a particular compound, molecule, or toxin, HyperTaste might not be the best tool to use. You may need to choose a different sensing mechanism—one that’s a bit more sensitive and has a lower limit of detection,” explained Ruch.

The HyperTaste project dates back to 2019

The invention of HyperTaste dates back to 2019, although it was only possible to analyze a few specific liquids back then. Now, it can analyze a wider range of substances.

“In the early days of the project, we had to manually dip the array of sensors several times into different liquids to collect our training data. Eventually, we moved to a robotic autosampler unit with the sensors mounted on it. The autosampler can work by itself 24/7 to dip the sensor into different liquids,” explained Ruch.

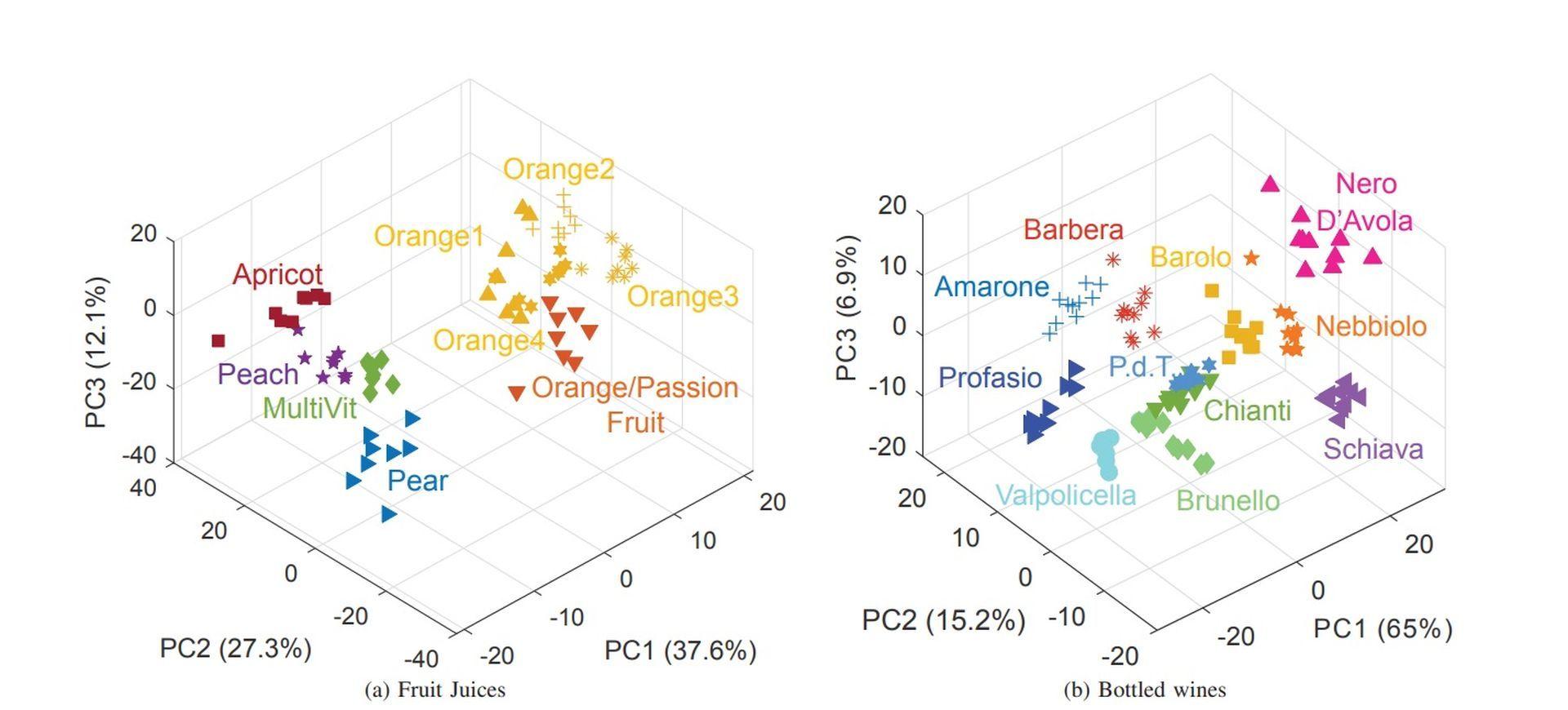

IBM has tested HyperTaste’s capacity to distinguish various kinds of bottled mineral water, identify fruit juices by kind, and rank wines by brand and origin. Ruch groups the future applications for HyperTaste into four categories: authentication to verify the source of liquids and weed out counterfeit goods; quality control to validate consistent beverage quality; innovation to develop new flavors and monitoring.

“The idea was to show that HyperTaste could autonomously monitor ocean chemistry along time and the route of travel to be able to make statements about things like ocean acidification. Some engineering had to be done to make sure the seawater could be pumped up from the ocean to be sampled on board, but the good news is that the system remained operational throughout the journey. We’re looking forward to dissecting the data once we have it,” explained Ruch.

IBM is investing in HyperTaste as part of a larger effort to speed up material discovery and creation.

“This kind of machine-assisted interpretation of measurement data could be useful for the lab of the future, and there’s a lot of potential to use machine learning in lab analytics. If a machine can help interpret measurements, then you can find out how to automatically synthesize compounds and instruct robotic labs to produce those compounds. You can generate new hypotheses about novel types of materials that could have better properties or be made from more sustainable substances. Accelerating the process of interpreting data can help automate the cycle of innovation,” said Ruch.

If you want to learn more about AI, check out the fantastic precursors of Artificial Intelligence. By the way, regulators are also very busy on this subject. Did you know Europe is preparing the EU AI Act?