Only a decade ago, to speak of Africa and technology would have seemed nonsensical. Today, it is part of a growing global conversation.

Mobile penetration rates have increased 19 percent annually over the past five years, making the continent’s technological future look especially promising. The use of mobile phones has opened up new opportunities for healthcare, education, and financial services. Kenya’s M-PESA, a micro-financing tool that allows users to deposit, withdraw and transfer money via their mobile, is a notable example of how technology is radically changing the lives of many Africans. Within just five years of its inception, M-PESA has over 17 million users and 31 percent of Kenya’s GDP travels through the system.

However, tools like M-PESA are only the beginning of what could be a comprehensive digital transformation. According to a report by the World Bank, penetration of an additional 10 percent in telecommunication services could see GDP growth from 0.73 percent and 1.38 percent in low-and-middle income African countries. Similarly, McKinsey Global Institute predicts that should broadband be embraced at the same pace mobile technology has, iGDP could account for as much as 10 percent of total GDP in Africa by 2025.

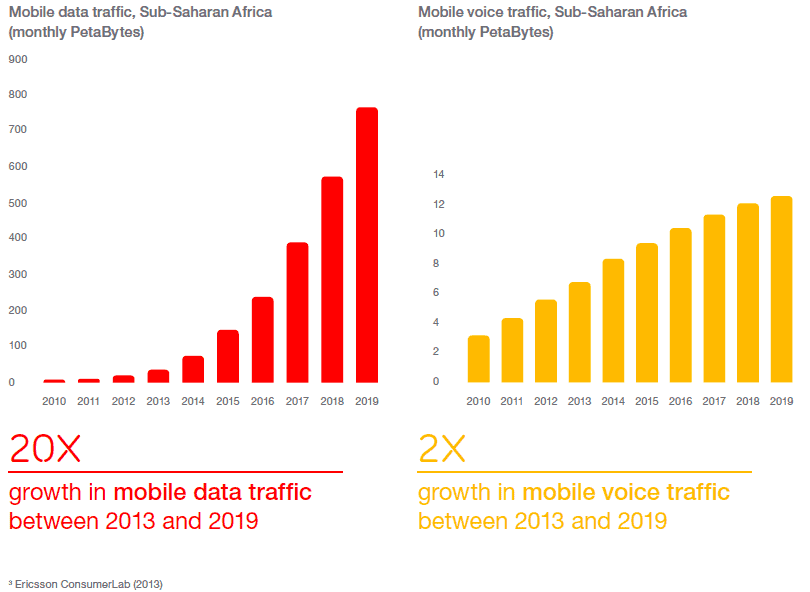

Moreover, big data is also gathering momentum in the continent. Ericsson released a report this week showing how mobile data traffic is averaging 76,000 TB a month, doubling from 37,000 TB a month produced in 2013. Data of this scale can have huge implications. Take, for example, how the collection of calling data in Haiti helped with disaster relief after the 2010 earthquake. Researchers from Karolinska Institute and Columbia University analyzed 2 million mobile phones to detect the pattern of population movements across the county, which was then handed to humanitarian agencies to predict and allocate resources effectively.

Helping with disaster relief is not the only way big data could transform Africa’s landscape. Wolfgang von Loeper, a farmer in South Africa, is months away from launching an app, my SmartFarm, which he argues can have a similar impact on agriculture on the region. His goal is to use agriculture-themed data (climate, soil information and disease) to help farmers make more informed decisions about irrigation, pest-control and fertilisation, effectively streamlining an industry that accounts for 32 percent of Africa’s labor force and 32% of its GDP.

Helping with disaster relief is not the only way big data could transform Africa’s landscape. Wolfgang von Loeper, a farmer in South Africa, is months away from launching an app, my SmartFarm, which he argues can have a similar impact on agriculture on the region. His goal is to use agriculture-themed data (climate, soil information and disease) to help farmers make more informed decisions about irrigation, pest-control and fertilisation, effectively streamlining an industry that accounts for 32 percent of Africa’s labor force and 32% of its GDP.

Examples of big data and its importance for socio-economic growth are rife. Still, these statistics and reports should not be met with unbridled optimism. There remains an important question to be considered — how do these statistics change when African nations are examined in isolation, rather than as a monolithic whole?

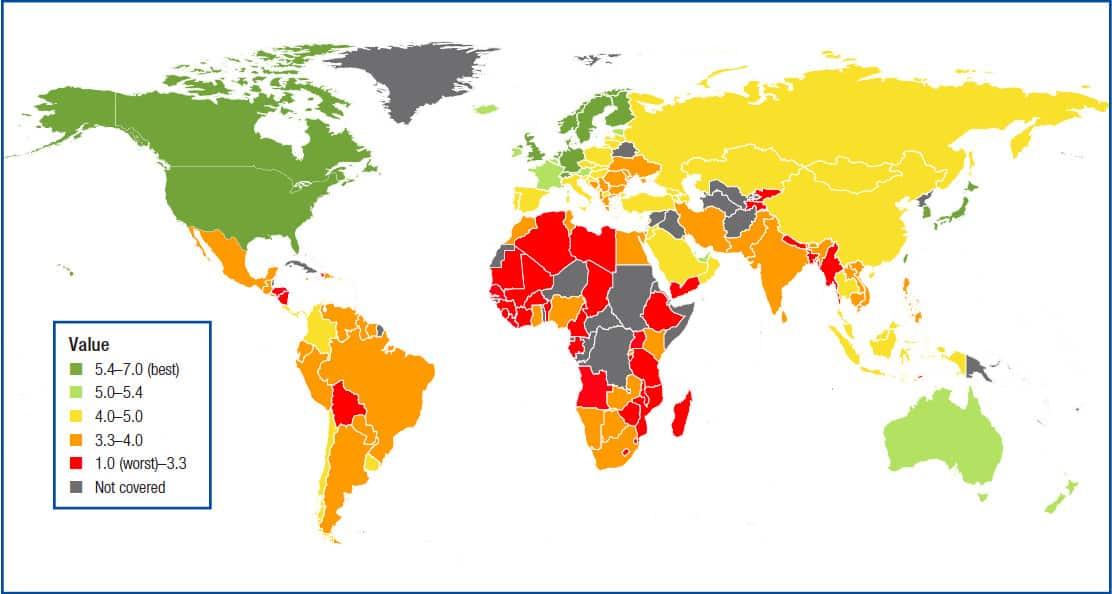

Between 1998-2008, $5 billion was invested annually in Africa’s telecommunications sector. This investment, however, was unevenly distributed in the continent; Nigeria and South Africa accounted for more than 60 per cent of this total. Moreover, this uneven distribution has been forecasted to continue. Future investment in broadband infrastructure for over 70 per cent of Sub-Saharan Africa is said to be commercially viable, but the numbers differ widely when analysed on a country-by-country basis – ranging from Swaziland and Mauritius at 100 per cent commercial viability to Democratic Republic of Congo and Liberia at 0 per cent. For countries in the latter category, government subsidies would need to be in excess of $199 million to generate any kind of commercial interest.

Technology giants like Google, Microsoft, and Facebook are crafting solutions to these gaps in accessibility. Innovative means of providing affordable internet access to the most remote crevices of the region, such as Google’s Project Loon, Microsoft’s experiments with “white spaces” to support broadband, and Facebook’s attempts to lower mobile data rates, show a fascination with what Africa could accomplish if it were to become universally connected.

But the reality is that while technological “hubs” like Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa can take quick and immediate advantage of technological investment in the area, countries facing large internet coverage gaps will be reliant on the development of the nascent projects mentioned above, along with radical economic and political reforms. These countries — the DRC, Liberia, Central African Republic, Gambia, Zimbabwe, Burundi among others — will become marginalised as they struggle to receive the right infrastructural investment, aid and innovations at the same pace as their neighbours. Meanwhile, the success of those countries that are economically stable and more populated will obfuscate the real picture, ultimately distorting the global perception of Africa’s “technology boom.”

All of this is to say, countries that stand to benefit most from innovative applications of data analytics – disaster relief, finance, agriculture and countless examples of benefits to other industry verticals — are not yet even on the technology, or data, map. As such, to speak of the continent’s growth without a nuanced understanding of its individual countries is becoming increasingly problematic.

Furhaad worked as a researcher/writer for The Times of London and is a regular contributor for the Huffington Post. He studied philosophy on a dual programme with the University of York (U.K.) and Columbia University (U.S.) He is a native of London, United Kingdom.

Furhaad worked as a researcher/writer for The Times of London and is a regular contributor for the Huffington Post. He studied philosophy on a dual programme with the University of York (U.K.) and Columbia University (U.S.) He is a native of London, United Kingdom.

Email: [email protected]

(Image Credit: Featured, International Communications Union; Image 1, Ericsson; Image 2, World Economic Forum)